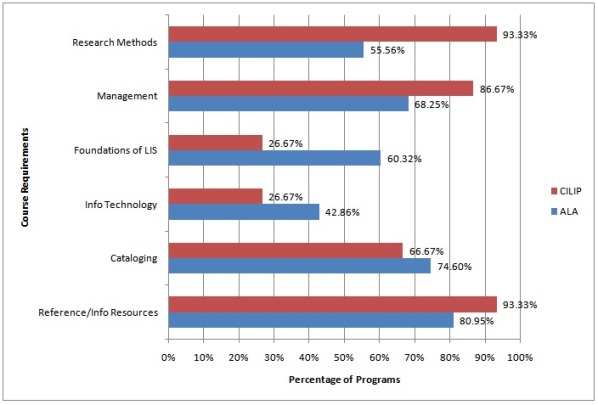

Assessing the Transferability of Library and Information Science (LIS) Degrees Accredited by the American Library Association (ALA) and the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP)AbstractThis paper aims to assess, through the use of surveys and data comparison, the transferability of Master's-level library and information science (LIS) degrees accredited by the American Library Association (ALA) and the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP). Data from this study shows that the ALA and CILIP expect nearly the same core competencies of their accredited graduates, and that graduates of CILIP-accredited programs tend to enter the work force with more practical experience. In addition, employers who have hired LIS graduates with foreign credentials report a high satisfaction in their international hires, as well as no major gaps in professional knowledge bases. Despite the apparent transferability of skills between organizations, the majority of job postings in the United States and Canada specifically require ALA-accredited degrees, whereas the United Kingdom (UK) typically recognizes and accepts ALA credentials and CILIP accredited degrees. This discrepancy in the acceptance of qualifications may be due to a lack of communication, but further research is needed to investigate this. IntroductionAs the Internet makes worldwide communication easier almost daily, and as libraries around the world aim to collaborate more and more toward common goals, it is increasingly important for librarians to have a global view of the profession. An understanding of the professional knowledge and techniques of colleagues around the world would contribute greatly to that view. To support collaboration and communication, professional organizations such as the American Library Association (ALA) and the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) sponsor roundtables, interest groups, and conferences to encourage international collaboration among their members. The ALA states that it "promotes the exchange of professional information, techniques and knowledge, as well as personnel and literature between and among libraries and individuals throughout the world" (American Library Association, 2011b, para. 1). One major method of gaining international experience and global context firsthand, working overseas, can prove to be quite difficult for librarians due to the question of degree equivalency. Undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral degrees in library and information science (LIS) are offered as programs worldwide. Many countries have their own accrediting organizations, and there are no universally agreed-upon guidelines in place for degree comparisons. In an effort to make it easier to transfer LIS credentials across borders, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) has drafted a set of guidelines for �transparency, equivalency and recognition of qualifications� (Weech & Tammaro, 2009, p. 1) for LIS professionals. Unfortunately, until these guidelines are put into practice by every LIS program, the reciprocity of foreign credentials is likely to remain a gray area. CILIP, the professional organization for librarians in the United Kingdom (UK), is one accrediting body that clearly states which international LIS degrees it recognizes as being comparable to those it has accredited: "graduate level qualifications from the USA, Canada, Australia and the EU members states are accepted in the UK. Other qualifications will have to be individually checked by CILIP" (Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, 2010, para. 1). On the same webpage, CILIP cites a reciprocal agreement with the ALA that deems LIS degrees accredited by both organizations valid for employment on either side of the Atlantic. Though no mention of a reciprocal agreement can be found on the ALA website, the ALA does claim to recognize CILIP-accredited degrees as "acceptable for employment in the United States" (American Library Association, 2011a, para. 11). The association; however, suggests that all degrees from non-US programs be evaluated (American Library Association, 2011a). In spite of this declaration that CILIP-accredited degrees are considered acceptable by the ALA, the majority of job postings for librarians in the United States (US) and Canada still require degrees from ALA-accredited LIS programs, and there have been instances of librarians with foreign credentials either being turned down for professional positions or having to earn a second LIS degree in order to gain professional employment in the US. In contrast, the vast majority of postings for professional librarian positions in the UK do not require LIS degrees accredited by one particular body; rather, they tend to mention such requirements as professional librarian, professional library or information management qualification, or other similar descriptions. This study aims to investigate the equivalency of CILIP- and ALA-accredited degrees as well as whether the discrepancies in what the accrediting bodies claim to accept for credentials do in fact make it more difficult for graduates of CILIP-accredited programs to gain professional employment in the US and Canada than it is for graduates of ALA-accredited programs to get hired in the UK. Data was gathered comparing LIS program curricula and the core competencies expected of holders of ALA- and CILIP-accredited degrees. In addition, surveys were distributed to (a) graduates of LIS programs accredited by both bodies, and (b) library hiring managers on both sides of the Atlantic to determine perceived transferability based on personal experiences. Literature ReviewThe topic of international librarianship has been widely discussed within the profession since 1877 (Abdullahi & Kajberg, 2004), and has recently become a hot-button issue as the impact of the Internet on worldwide communication continues to grow. While the literature offers plenty of views on the topics of international and comparative librarianship, little research has been done on the comparability of LIS programs around the world, and none to date has been published specifically on the equivalency of degrees accredited by ALA and CILIP. Many members of the profession have stressed the importance of global cooperation among librarians and called for the worldwide exchange of professional knowledge and techniques (Abdullahi & Kajberg, 2004; Abdullahi, Kajberg, & Virkus, 2007; Cveljo, 1997; de la Pena McCook, Ford, & Lippincott, 1998; Friend, 1999; Kesselman & Weintraub, 2004; Long, 2001; Pors, 2007).Working in libraries abroad would be an advantageous way for librarians to meet these goals through networking, skills learned on the job, and experiencing the concept of the library through the context of other cultures. Since being able to ascertain the equivalency of LIS degrees would make it easier for librarians to acquire jobs in other countries, covering this topic in the literature would be beneficial to the profession. Searches using a combination of keywords such as "international,""global," "credentialing," "accreditation,""LIS," "library," "education," "CILIP," "ALA," "librarians," "United States," "United Kingdom," "Canada," and "abroad" in EBSCO, ebrary's Library and KM Center, Emerald Library Suite, OCLC, MIT's Vera Multi-Search database, and yielded no comparisons of LIS credentialing in the UK, US, and Canada. Researchers have, however, examined the issue of foreign LIS credentialing in general. Burtis, Hubbard, and Lotts (2010) analyzed 136 job postings for academic librarian positions in the US in an effort to ascertain the availability of jobs for applicants with non-ALA-accredited LIS degrees. Dowling (2007) acknowledges that the ALA has amended its policy regarding the equivalency of international credentials but argues that the organization needs to take a more active role in alerting US libraries of the change, since many still list ALA-accredited degrees as a requirement for professional positions. He also cites a lack of international cooperation on the topic, and calls for the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) to become more involved in the standardization of professional qualifications. Similarly, Tammaro (2006) urges library associations and accrediting bodies to develop more specific evaluations of LIS programs in order to make the degrees more internationally recognizable. The issue of international credentialing is a gray area not just in librarianship, but in other professions as well. Clawson (2000) offers advice on how to deal with the obstacles of hiring counselors with foreign credentials, and Lang and Summerson (2008) describe the efforts of the Association of School Business Officials (ASBO) in determining how to standardize international qualifications in the business field. Due to the gap in recent literature relating to ALA-accredited librarians working in the UK or CILIP-accredited librarians working in the US and Canada, studies pertaining to those librarians taking positions in other countries could provide more general information on transitioning to jobs overseas. Collier (2007) and Jefcoate (2007) both advise UK librarians who are planning to take on management positions on the European continent on how to handle obstacles such as language barriers, finding housing, and differences in theory and policy. Several librarians have written of their experiences in moving from Australia to take positions in the UK and Canada, and provide useful information on the transition of adapting to libraries in these countries (Hayes, 2007; McKnight, 2007; Schmidt, 2007; Williamson, 2007). Mood (1985), Williams (1985), and Williamson (1988) provide examples of American librarians working in the UK, but given the advances in library practice and technology since the 1980s, their information is outdated. Several researchers have examined LIS programs through the years, exploring such issues as curriculum trends and how employers view the value of the education (Chu, 2006; Conant, 1980; Parr & Wainwright, 1978). Blankson-Hemans and Hibberd (2004) surveyed librarians and LIS faculty to determine how well the curricula of LIS programs prepared future librarians for jobs in the commercial sector. Though they gathered data from librarians in both the US and UK, their study did not touch upon the issue of degree equivalency. In their 2002 study, Mortenzaie and Naghshineh examined and compared graduate LIS programs in the UK, US, India, and Iran. Their aim was to restructure LIS programs in Iran, and they did not discuss the transferability of degrees. While the research that has been published on the topics of international credentialing, librarians working overseas, and LIS programs in general is helpful in gaining a basic understanding of the challenges involved in acquiring employment abroad, there still remains an absence of information about the equivalency of LIS credentials worldwide. This study is carried out in an effort to fill part of the gap that deals with the transferability of accredited LIS degrees earned in the UK,US, and Canada. Research MethodsTwo methods were employed in order to assess the transferability of LIS degrees earned at programs accredited by the ALA and CILIP. First, both the core competencies as defined by each accrediting body and the core curricula from all ALA- and CILIP- accredited programs were compared in order to determine the similarity of the knowledge base expected of LIS graduates in the US, Canada, and the UK. Second, two surveys were distributed to four populations. One, composed of eleven questions, was made available to graduates of ALA-accredited programs who have been employed, or who have applied for employment, in libraries in the UK, as well as to graduates of CILIP-accredited programs who have worked, or who have applied to work, in US or Canadian libraries. The second survey, also composed of eleven questions, was made available to UK-based library employers who have hired or considered hiring LIS graduates with ALA-accredited degrees, as well as to library employers in the US and Canada who have hired or considered hiring LIS graduates with CILIP-accredited degrees. Each survey employed a combination of multiple-choice questions, Likert scale ratings, and open-ended questions with the aim of gathering (a) examples of the successes and challenges of acquiring and/or transitioning to library employment overseas, and (b) opinions on the transferability of LIS degrees based on those examples. Both surveys were hosted through SurveyGizmo. Corresponding URLs and a brief explanation of the project were emailed to potential participants via listservs affiliated with ALA, CILIP, the Canadian Library Association (CLA), and the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). Additional requests were distributed via the Twitter and blog of the Qualifications Advisor at CILIP, as well as through ALA Connect discussion pages and Facebook groups for LIS alumni. All respondents were self-selected based on their interest in the postings, and participation was completely voluntary. Core Competencies of LIS ProgramsA comparison of the core competencies of ALA and CILIP shows that the two organizations hold very similar expectations for graduates of their accredited programs. Though presented in two visually distinct ways and employing slightly different language, ALA�s Core Competencies and CILIP's Body of Professional Knowledge (BPK) outline essentially the same knowledge base that is expected of new members of the profession. Adopted in January 2009, the most recent edition of the ALA's Core Competencies "defines the basic knowledge to be possessed by all persons graduating from an ALA-accredited master's program in library and information science" (American Library Association, 2009, p. 1). This basic knowledge is presented in an outline form, broken down into eight categories: (1) Foundations of the Profession, (2) Information Resources, (3) Organization of Recorded Knowledge and Information, (4) Technological Knowledge and Skills, (5) Reference and User Services, (6) Research, (7) Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, and (8) Administration and Management. Each category is then itemized into specific areas with which LIS graduates are expected to be familiar. CILIP's BPK, adopted in November 2004, is portrayed by three concentric circles, each representing a different area of professional knowledge. At the center lies the Core Schema, which holds the concepts and processes that are considered �central to the specialist knowledge and skills exercised by the information professional� (Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, 2004, introduction). Those central components are further explained by a diagram that shows how the processes link the various concepts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Diagram of the BPK's Core Schema. From Body of Professional Knowledge (p. 4), by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, 2004, London: CILIP. Copyright 2004 by CILIP. Reprinted with permission.

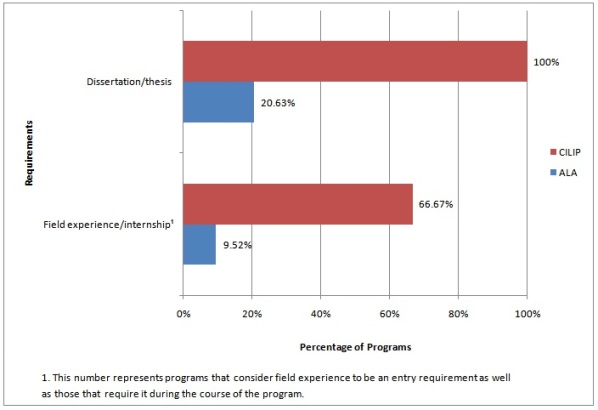

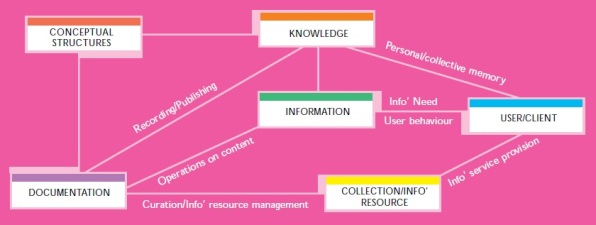

Outside of the Core Schema lies the Applications Environment, which serves to place the components of the Core Schema into various contexts of the information profession: ethical frameworks, legal dimensions, information policy, information governance, and communications perspectives. The outermost circle, labeled Generic and Transferable Skills, consists of proficiencies expected of members of the LIS profession that are also useful beyond the field: computer and information literacy, interpersonal and management skills, marketing ability, training and mentoring skills, and familiarity with research methods. Upon close inspection of each organization�s core competencies, it becomes clear that the professional expectations of ALA and CILIP are nearly identical. In fact, the only knowledge base components that are noticeably different are the history of the profession, which ALA expects under its Foundations of the Profession category but CILIP does not explicitly mention, and the concept of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning which, again, is listed by ALA but not addressed directly by CILIP. CILIP does encourage continuing professional development, and requires evidence of it for librarians who want to become chartered members of the organization (Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, 2011a). Thus it can be assumed that CILIP holds continuing education in high regard even though the BPK does not mention it specifically. Core Courses of LIS ProgramsAt the time of research, the ALA accredits 63 Master's-level LIS programs and CILIP accredits 17 Master's-level programs; however, only 15 CILIP-accredited programs are included in this study. The program at the Cologne University of Applied Sciences in Germany is omitted because the scope of this study's survey is limited to the UK, Canada, and the US. Another program, at the University of West London, is omitted because it is not currently active � though CILIP continues to recognize the credentials of its previous graduates (Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, 2011b) � and also because no information about the program can be found on the university's website. Using the common competencies of ALA and CILIP as a guide, the curricula of all 78 programs included in this study were examined in order to establish which areas of the shared professional knowledge base are most represented in required courses. The number of required courses � also referred to as core courses in ALA-accredited programs and core or required modules in CILIP-accredited programs � range from two to nine and vary in content. The percentages of programs that have clearly stated required courses related to the shared competencies are shown in Figure 2. For the purpose of this study, courses centered on reference and information services and those dealing with information resources are grouped into the same category, since many programs require survey courses touching upon both topics. From the data shown in Figure 2 it can be deduced that, though the core competencies for ALA and CILIP are nearly identical, the LIS programs aiming for those competencies vary significantly in terms of what related courses are required. The discrepancies in what ALA- and CILIP-accredited programs require for courses vary greatly too, though neither type of program lags behind the other in terms of covering competency areas. ALA-accredited programs outnumber those that CILIP accredits in three competency areas, while CILIP-accredited programs outnumber ALA-accredited ones in the other three areas. The most significant numerical differences in required courses are for Research Method classes and those dealing with the Foundations of LIS. There is a 33.65 percent difference in the number of ALA-accredited programs that require Foundations courses as opposed to CILIP-accredited programs. This discrepancy could be expected, since �Foundations of LIS� is not a competency that is mentioned specifically in the BPK. However, the 37.77 percent difference in programs requiring Research Methods courses is surprising, given that the ALA dedicates one of the eight competency categories to the subject. In addition to course requirements based on competency areas, many programs also require either practical experience in the field or a thesis or capstone project. Some programs require both. The percentages of Master's-level programs with these requirements are displayed in Figure 3. From the data shown in Figure 3, it can be presumed that CILIP-accredited programs place significantly greater emphasis on practical experience in the field than programs accredited by the ALA do. In fact, nearly half (46.67 percent) of CILIP-accredited programs require that applicants have previous related work experience before they can be admitted. Thus it can be argued that graduates of CILIP-accredited programs enter the job market with more hands-on knowledge of the field. Since ALA-accredited LIS graduates� previous work experience is unknown and therefore not included in the data, this argument is not thoroughly supported. Another assumption from the data in Figure 3 is that CILIP-accredited programs are more academically rigorous than those accredited by the ALA, since 100 percent of Master's-level programs in the UK require dissertations of 15,000 words or more. It is noteworthy to mention that students in CILIP-accredited programs who do not complete a dissertation still graduate with what is called a Postgraduate Diploma, or PG Dip, and are still considered by CILIP to be professionally qualified. The PG Dip is not recognized by the ALA as equivalent to an ALA-accredited Master's degree, even though graduates of most ALA-accredited Master's programs are not required to complete a dissertation and are therefore earning the CILIP equivalent of a PG Dip. Survey ResultsAs mentioned above in the Research Methods, two surveys were made available to four populations with the aim of gathering (a) examples of the successes and challenges of acquiring and/or transitioning to library employment overseas, and (b) opinions on the transferability of LIS degrees based on those examples. The surveys were hosted on SurveyGizmo.com and were open for approximately two weeks between April 18 and April 30, 2011. Ninety-four complete responses were collected for the employee survey, and thirteen complete responses were collected for the employer survey. The employer survey, intended for respondents who have hired or have considered hiring job applicants with foreign credentials, asked respondents to rate their satisfaction with the applicants they had hired from overseas, and to comment on any gaps in professional knowledge they noticed in foreign-credentialed employees. The survey also asked the respondents if they had ever turned down applicants because of their foreign credentials. Of the 13 respondents, six (46.2 percent) are employed in Canada, five (38.5 percent) are employed in the US, and two (15.4 percent) are employed in the UK. Three of the 13 (23.08 percent) responded that they had never hired job applicants with foreign credentials, and one of those three � an employer in Canada � indicated that he or she had turned down applicants specifically because of their foreign credentials. Of the 10 respondents who had hired applicants with foreign credentials, nine (90 percent) reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the ease and speed to which those foreign-credentialed employees adjusted to their work environments; the remaining one respondent reported feeling neutral. Six of the 10 employers who had hired applicants from overseas work in academic libraries, one works in a public library, one in a law library, one in a museum, and one at a cataloging agency. In terms of any noticed gaps in the foreign-credentialed employees� professional knowledge bases, one respondent cited a lack of knowledge of local resources and contacts, while another mentioned a lack of �knowledge of our technology environment and library practices in Canada. . . However, that knowledge could be obtained [once on the job].� One respondent, an academic librarian in the US, commented that he or she had noticed firsthand the difficulties that foreign-credentialed librarians face when trying to find work in the US: "Over the years, I have seen many foreign LIS professionals languish in paraprofessional positions for which they are over-qualified and over-educated. In my experience, however, libraries in the U.S. are not willing to hire foreign graduates for MLS-level positions because foreign programs are not ALA-accredited. So, MLS-level foreign grads can't get MLS-level positions in the U.S.!" From the data gathered in this survey, it can be inferred that employers who hire employees with foreign credentials tend to be satisfied with the speed with which those employees adjust to working overseas, and no major gaps seem to exist in core areas of the professional knowledge base. The data from this survey may be biased due to the low number of respondents, and unequal representation of employers from varying types of libraries or the countries represented. The employee survey, intended for respondents who have worked, or have applied to work, overseas, posed questions regarding where LIS degrees were earned, whether the respondents have ever applied for work overseas, what reasons were provided by employers if the respondents were not hired, and what gaps, if any, in their professional knowledge base the respondents noticed upon successful hire overseas. Out of the 94 complete responses to this survey, 45 (49.7 percent) respondents earned their LIS degree in the US, 29 (30.9 percent) received their LIS degree in the UK, and 20 (21.3 percent) earned their LIS degrees in Canada. Only one respondent earned an LIS degree that was unaccredited. Out of those 93 accredited graduates, 36 (38.71 percent) reported having applied for library jobs overseas; 19 ALA-accredited graduates and 17 CILIP-accredited graduates. Of those 36, 22 (61.11 percent) responded that they had been successful in landing employment abroad. The number of ALA-accredited graduates who reported that they were hired in the UK totals 16 out of the 19 (81.24 percent), while six out of the 17 (35.29 percent) CILIP-accredited graduates reported being successfully hired in either the US or Canada. Of the successful ALA-accredited applicants, 10 received their LIS degrees in the US, and six received their degrees in Canada. As for the reasons applicants were given if they were not hired, four reported being considered under-qualified, two were considered over-qualified, one was turned down for not having a proper visa or working permit, and one explained that he or she did not have enough relevant experience or local knowledge. Sixteen respondents reported that no reasons had been given, and, interestingly, no one responded that possession of foreign credentials was the reason why a position was not offered. (The data from this question was not calculated into percentages because respondents were able to select more than one response). Despite no respondents in the employee survey listing foreign credentials as a reason for being denied employment overseas, several people did submit comments on the topic via email. Three, who identified themselves as American citizens, described experiences in which they earned LIS degrees in the UK, and then returned to the US to find that libraries would not hire them with their CILIP credentials. One of these respondents commented that library administrators told him that, �non-ALA degrees would not even be considered, regardless of [the] reciprocity which CILIP currently claims.� Another respondent, who identified herself as a lecturer at one of the CILIP-accredited programs in the UK, shared that a few American graduates of the program had reported also being denied employment upon returning to the States. In contrast, two respondents with non-CILIP credentials shared that they were able to find professional jobs in the UK without any difficulty. Thus, although not reflected in the statistical survey data, it is clear that foreign credentialing is indeed an issue when it comes to professional LIS employment in the US. Given the data from this employee survey, it can be surmised that graduates of ALA-accredited programs are more successful at acquiring jobs overseas in the UK than CILIP-accredited graduates are in the US or Canada. According to the data, this assumption is not due to the issue of foreign credentialing. The data in this survey may be skewed due to a survey flaw relating to an omitted negative response choice for the question dealing with reasons given for why applicants were not hired, as well as unintentional ambiguity in a few of the other questions, which resulted in some conflicting numbers. These flaws should be taken into consideration when considering the resulting data. In addition to the survey flaws mentioned above, there were some limitations in the research process that also may skew the data of both surveys. Before the surveys were launched, the Institutional Review Board of Southern Connecticut State University had to approve all questions included, as well as the methods proposed to gather the survey data. As part of this requirement, all media through which the surveys would be advertised had to be approved in writing, and many listserv and message board moderators did not respond to permission requests. Thus, the surveys were only advertised through the means for which permission had been granted, which significantly limited the number of possible respondents. Also, as this study constituted a school project that included deadlines, additional surveys and other follow-ups that could have improved the response rates were not feasible within the time limits. Conclusion and Further DiscussionSeveral conclusions may be drawn based on the data gathered in this study. First, ALA and CILIP expect essentially the same of their LIS graduates, as their core competencies are nearly identical. Second, though Master's-level LIS programs accredited by the ALA and CILIP may differ significantly in terms of core course requirements, neither type of program appears to consistently touch upon all core competency areas in their required courses, and in general, neither type of program consistently touches upon more competency areas in their required courses than the other. Third, most ALA-accredited Master's degrees are effectively the equivalent of CILIP-accredited PG Dips, and graduates of CILIP-accredited programs are more likely to have more practical experience in the field. If all the above conclusions are true, then ALA-accredited Master's degrees appear to be in no way superior to CILIP-accredited Master's degrees, and in fact it is expected that graduates on both sides of the Atlantic are entering the job market with comparable bases of professional knowledge. In addition, data from this study's surveys shows that employers on both sides of the Atlantic tend to be happy with foreign-credentialed employees, and that those with foreign credentials show no major gaps in professional knowledge. Why, then, are so many American and Canadian libraries excluding potential job applicants with CILIP-accredited degrees? The survey data shows that graduates of CILIP-accredited programs are indeed significantly less successful in finding employment across the pond than their ALA counterparts. If the ALA claims to promote �the exchange of professional information, techniques and knowledge, as well as personnel . . . throughout the world� (American Library Association, 2011b, para. 1), then why does the organization not make a greater effort to increase diversity in American and Canadian libraries by making it easier for foreign-credentialed librarians to be hired there? Perhaps the issue here is one of communication. Data from this study shows that several LIS students pursued Master's degrees in the UK due to CILIP's statement of a reciprocal agreement with the ALA regarding credentials, only to find that many libraries in the US and Canada do not recognize CILIP-accredited degrees. In addition, Dowling (2007) explains that the ALA has indeed changed its policies to be more accommodating of foreign credentials, but that the organization does not communicate well enough with human resources departments to make it better known that the policies have changed. It would certainly improve the LIS profession if organizations such as ALA and CILIP increased their communication, so that confusion about degree transferability does not continue to be perpetuated. Due to the limitations noted in this study, additional research is needed to collect the experiences and opinions of a larger range of respondents, as well as to perform a deeper investigation of LIS program curricula in order to further assess the comparability of ALA- and CILIP-accredited programs. ReferencesAbdullahi, I., & Kajberg, L. (2004). A study of international issues in library and information science education: Survey of LIS schools in Europe, the USA and Canada. New Library World, 105(9/10), 345-356. Abdullahi, I., Kajberg, L., & Virkus, S. (2007). Internationalization of LIS education in Europe and North America. New Library World, 108(1/2), 7-24. doi: 10.1108/03074800710722144. American Library Association. (2011a). Foreign Credentials Evaluation Assistance: Job Seekers. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/ala/educationcareers/employment/foreigncredentialing/forjobseekers/index.cfm American Library Association. (2011b). Issues & Advocacy: International Issues. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/ala/issuesadvocacy/international/index.cfm American Library Association. (2009). ALA�s Core Competences of Librarianship. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/ala/educationcareers/careers/corecomp/corecompetences/finalcorecompstat09.pdf Blankson-Hemans, L., & Hibberd, B. J. (2004). An assessment of LIS curricula and the field of practice in the commercial sector. New Library World, 105(7/8), 269-280. doi: 10.1108/03074800410551020 Burtis, A. T., Hubbard, M. A., & Lotts, M. C. (2010). Foreign LIS degrees in contemporary US academic libraries. New Library World, 111(9/10), 399-412. doi: 10.1108/03074801011089323 Chu, H. (2006). Curricula of LIS programs in the USA: A content analysis. In Khoo, C., Singh, D., & Chaudhry, A. S. (Eds.), Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Conference on Library & Information Education & Practice (A-LIEP 2006), Singapore, 3-6 April 2006 (pp. 328-337). Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.89.1470&rep;=rep1&type;=pdf Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (2004). Body of Professional Knowledge. Retrieved from BPK.pdf">http://www.cilip.org.uk/sitecollectiondocuments/PDFs/qualificationschartership/BPK.pdf Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. (2010). Qualifications from Overseas. Retrieved from http://www.cilip.org.uk/jobs-careers/qualifications/pages/overseas.aspx Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (2011a). Five steps to Chartership. Retrieved from http://www.cilip.org.uk/jobs-careers/qualifications/cilip-qualifications/chartership/pages/stepguidecharter.aspx Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (2011b). London: courses accredited by CILIP. Retrieved from http://www.cilip.org.uk/jobs-careers/qualifications/accreditation/courses/Pages/london.aspx Clawson, T. W. (2000). Expanding professions globally: The United States as a marketplace for global credentialing and cyberapplications. In Bloom, J. W. & Walz, G. R. (Eds.) Cybercounseling and cyberlearning: Strategies and resources for the Millennium. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. Collier, M. (2007). Moving on: Transferability of library managers to new environments. Library Management, 28(4/5), 191-196. doi:10.1108/01435120710744137 Conant, R. W. (1980). The Conant report: A study of the education of librarians. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Cveljo, K. (1997). Internationalizing LIS degree programs: Benefits and challenges for special librarians. Information Outlook, 1(10), 34-38. De la Pena McCook, K., Ford, B. J., & Lippincott, K. (1998). Libraries: Global reach � local touch. Chicago: American Library Association. Dowling, T. (2007). International credentialing, certification, and recognition in the United States. New Library World, 108(1/2), 79-82. doi:10.1108/03074800710722199 Friend, F. (1999). Libraries of one world: Librarians look across the ocean. Collection Management, 24(3/4), 281-287. doi:10.1300/J105v24n03_06 Hayes, H. (2007). A Scottish enlightenment. Library Management, 28(4/5), 224-230. doi:10.1108/01435120710744173 Jefcoate, G. (2007). Managing libraries overseas: Some challenges and opportunities. Library Management, 28(4/5), 207-212. doi: 10.1108/01435120710744155 Kesselman, M. A., & Weintraub, I. (2004). Global librarianship. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Lang, S., & Summerson, T. (2008). International credentialing: An opportunity or a threat? School Business Affairs, 74(1), 27-29. Long, S. (2001). Library to library: Global pairing for mutual benefit. New Library World, 102(3), 79-85. doi: 10.1108/03074800110383741 McKnight, S. (2007). The expatriate library director. Library Management, 28(4/5), 231-241. doi: 10.1108/01435120710744182 Mood, T. A. (1985). An exchange in England [Abstract]. Reference Services Review, 13(3), 9- 12. doi: 10.1108/eb048906 Mortezaie, L., & Naghshineh, N. (2002). A comparative case study of graduate courses in library and information studies in the UK, USA, India and Iran: Lessons for Iranian LIS professionals. Library Review, 51(1), 14-23. doi: 10.1108/00242530210413904 Pors, N. O. (2007). Globalisation, culture and social capital: Library professionals on the move. Library Management, 28(4/5), 181-190. doi: 10.1108/01435120710744128 Schmidt, J. (2007). Transplanting a Director of Libraries: The pitfalls and the pleasures. Library Management, 28(4/5), 242-251. doi:10.1108/01435120710744191 Tammaro, A. M. (2006). Quality assurance in Library and Information Science (LIS) schools: Major trends and issues. In Woodsworth, A. (Series Ed.), Advances in Librarianship: Vol. 30 pp. 389-423. doi:10.1016/S0065-2830(06)30012-8 Weech, T., & Tammaro, A. M. on behalf of IFLA's Education and Training Section. (2009, December 30). Retrieved from http://www.ifla.org/files/set/Guidance_document_for_recognition_of_qualifications_2009-3.pdf Williams, R. V. (1985). Recent studies and writings: American librarians abroad, 1978-1985. Leads, 27, 3-5. Williamson, L. (1988). Going international: Librarians� preparation guide for a work experience/job exchange abroad. Chicago: American Library Association. Williamson, V. (2007). Working across cultures. Library Management, 28(4/5), 197-206. doi: 10.1108/01435120710744146 Author's BioDana Goblaskas recently completed her MLS degree at Southern Connecticut State University (New Haven, CT). She initially wanted to pursue her library degree at University College London, but decided against doing so for fear that libraries in the US wouldn't recognize a CILIP-accredited degree. She works as an archives collections assistant at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. |

Contents |

Copyright, 2013 Library Student Journal | Contact

international · peer reviewed · open access

international · peer reviewed · open access